Executive Function & Metacognition

Executive Function (EF) and Metacognition (MC) are foundational skills that support learning, behaviour, and emotional regulation. EF includes the brain’s ability to plan, focus attention, manage emotions, and shift between tasks, skills governed by the prefrontal cortex (Blair, 2017).

Metacognition refers to the ability to reflect on and direct one’s own thinking and learning strategies (Roebers, 2017). EF and MC underlie behaviour and learning (Blair, 2017; Roebers, 2017). Students with EF challenges, often those with ADHD, learning differences, or trauma histories, may struggle with task initiation, organization, or emotional control. These difficulties are sometimes misinterpreted as laziness or defiance when, in truth, they reflect real neurological delays (Barkley, 2009, 2012; Calderon, 2023).

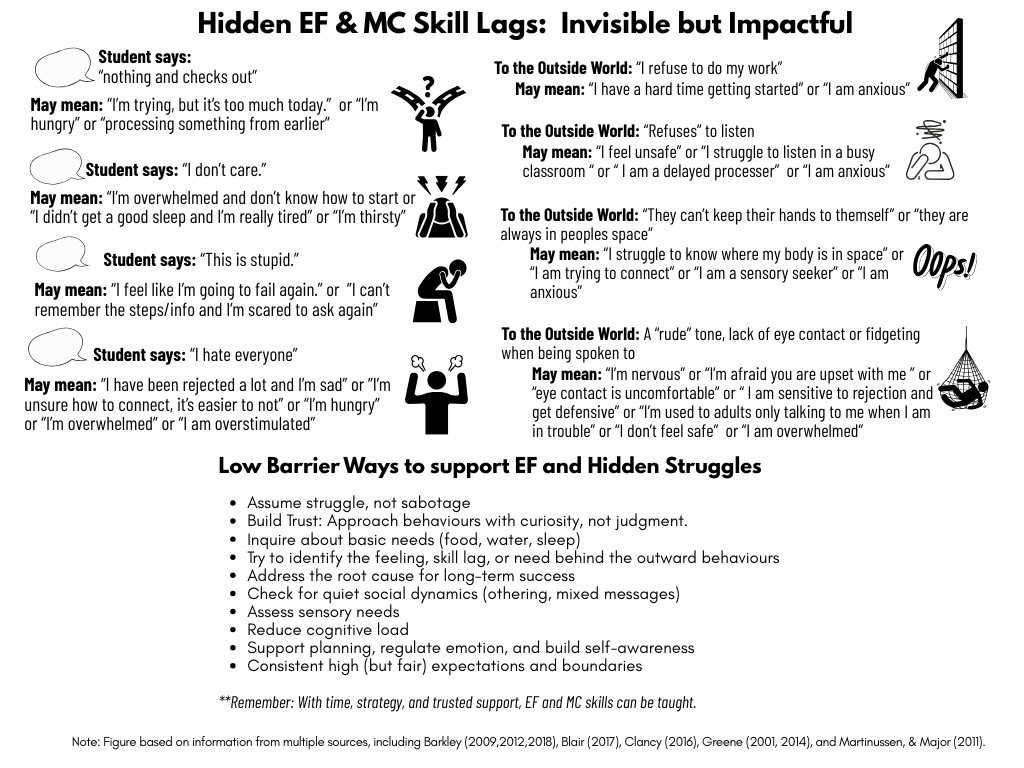

Hidden Executive Function Lags & Metacognition

Stress also impairs EF; neurodivergent students face an increase in redirection, rejection, and consequences received due to misunderstood skill gaps, leading to stress and further executive dysfunction (Barkley, 2009, 2018; Calderon, 2023). Metacognition must be explicitly taught. Neurodiverse learners in particular need consistent, targeted support to build these skills, and explicitly teaching EF and MC promotes equity (Stanton et al 2021).

As introduced in Section 1, Executive Function (EF) and Metacognition (MC) are foundational capacities that support learning, behavior, and emotional regulation. Many students who appear inattentive, disorganized, or oppositional may be navigating unseen EF and MC skill gaps, such as planning, self-monitoring, and emotional control, linked to the prefrontal cortex (McLeod, 2023; Couzens et al., 2015).

These difficulties often arise from genetics, trauma, chronic stress, or asynchronous development and can be misinterpreted due to inconsistent performance (Barkley, 2009; Couzens et al., 2015). A student may succeed one day and struggle the next; not due to lack of effort, but due to cognitive overload or unmet regulatory needs (McLeod, 2023; Pineda-Alhucema, 2018). Such fluctuations are frequently misread as defiance or disinterest, contributing to inaccurate labels like “at risk” (Barkley, 1997, 2009; Martinussen & Major, 2011).

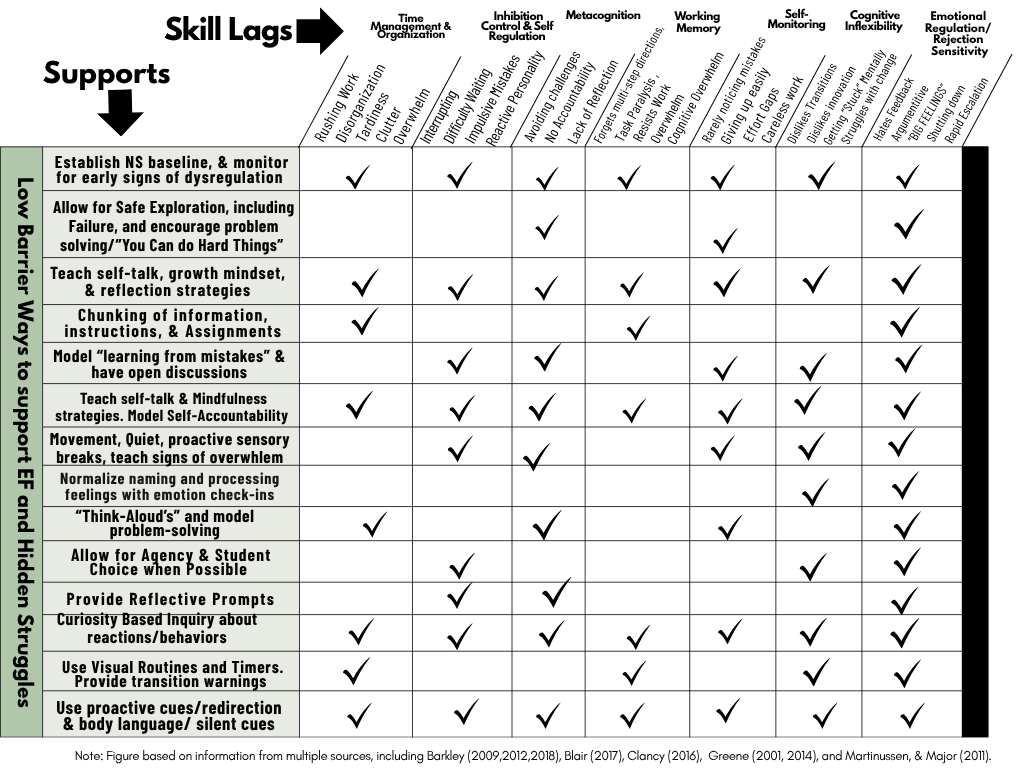

Supporting Executive Function Skills in the Classroom

When classroom demands exceed internal capacity, even motivated students may appear resistant (Barkley, 2009; McLeod, 2023). Classrooms that support regulation through mindfulness, movement, and consistent routines create conditions for EF and MC development and because these challenges don’t always show up in test data, students may internalize failure despite genuine effort (Stanton et al., 2021).